A discursive design concept.

We created a Climate Futures participatory workshop to open up space for diverse perspectives and help people envision positive post-climate change futures that match their values.

Suppose it is 2040, and we live in a world in which we've "beat" climate change.

Collaborators

Dinah Coops: Generalist

Julie T. Do: Generalist

Kyle Thomas: Researcher

Challenge.

Where we started

How might we help those in our communities who are concerned about climate change to be more involved?

From January to June 2020, our UW HCDE capstone team researched and iterated on ideas and design tools surrounding people’s involvement in climate change issues. Our project spanned the outbreak of Covid-19 and the civil rights reawakening with Black Lives Matter at the forefront. Both global events helped frame our project around Climate Justice.

Process.

Secondary research

Primary research

• subject matter expert interviews

• mixed methods survey

• co-design sessions

• observations

Analyze data

Focus users/create journey map

Ideate/design/iterate

Outcome.

We interpreted our research 2 different ways, leading to two branches of work:

1. Branch that focused on community engagement.

2. Discursive branch that focused on participant reflection and conceptualizing the systemic roots of climate issues. The work on this site reflects this branch and the cumulation of this work is the Climate futures workshop anthology and guidebook.

A wicked problem space.

What is a wicked problem?

A wicked problem is one that is intertwined with many other systemic problems and for which there are no right or wrong answers, just ones that are better or worse.

And, why discursive design? Discursive methods and design are well suited to reflection and the unpacking wicked problems. Developing this workshop, we took a critical, discursive lens to unpack the systemic roots of climate issues.

Why the name solastalgia?

Solastalgia is a form of emotional or existential distress caused by environmental change.

The wicked problem of climate change can often feel insurmountable and hopeless, but in order to create change, we must believe that change is possible. With this project, we’ve strived to help others conceptualize a complex problem, expand imaginaries of possible futures, and above all, provide hope.

Hope in the climate movement.

A few of our early influences included the Green New Deal and AOC's A letter from the future, Superflux's STARK CHOICES, a podcast with Saul Griffith, and Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass. As our project progressed, we also drew inspiration from the solarpunk movement, Julia Watson's Lo—TEK: Design by Radical Indigenism.

“...Crafting positive or utopian futures is really hard and valuable work at this particular moment. There’s a tremendous amount of energy expended in our society today to block the exploration of meaningful alternatives to ‘the way things are.’ Things are not getting better, the status quo is not fixing the problem, and we don’t have time for the luxury of self-pity.”

— Adam Flynn on Solarpunk, 2015

Relationship map

Who are we designing for?

As our research and critical thinking developed, our user focus evolved.

Initially we moved through many iterations of possible “target users” and relationship maps, but after putting together our research findings, we became interested in how people concerned about climate change envision positive futures and find their voice in the climate change movement.

Overview

Formative research methods.

In the early stages of our project, we conducted formative research using subject matter expert interviews, a survey, co-design sessions, and observations of the climate community.

1. Subject matter expert interviews

From February-April, we conducted 6 subject matter expert (SME) interviews from organizers and leaders within the climate movement.

2. Survey

In April, we deployed a mixed-methods survey featuring 22 questions related to the climate crisis. We collected and analyzed 153 responses.

3. Co-design sessions

In April, we conducted 1 pilot and 3 co-design sessions with 14 participants. Participants were drawn from Washington state and unfortunately did not represent racial or socioeconomic diversity.

4. Observations

Throughout the project, we participated in the climate movement, first offline, and then online.

Research findings.

Subject matter expert interviews and co-design sessions top findings.

Climate and systemic issues intersect with one another.

Building coalitions amplifies voices, builds perspective, and creates solidarity.

Climate issues need to be reframed to match the values of the audience.

A moral imperative provides the vision to drive actions.

Envisioning a better future is often easier with a different perspective or cultural worldview.

Fun, fun, fun, fun! (If it’s fun, people will come.)

Those who focus on systemic issues may be more motivated to build coalitions and try to understand different perspectives

Our early SME interviews and co-design sessions provided qualitative data to analyze and build on. We used Miro to create affinity diagrams and map themes for both of these methods. Overall we found large agreement in the findings between both sets of participants.

Respondents were climate crisis believers who feel angry and frustrated, are actively engaged in content and initiatives and believe in collective and legislative action as solutions.

Key survey finding.

153 survey respondents were involved in 96 different climate-related organizations. This demonstrates significant diversity in interests and approaches. This finding led us to reframe the “divisiveness” of the climate movement as “diversity instead.”

Who is left out?

“Between the statistical image of the most hard hit... it begins to become clear that although we all inhabit the same ecological niche, we don’t really share one climate.”

— Ajay Singh Chaudhary (2020)

Additionally, the racial gaslighting from white, privileged environmentalists makes the mainstream climate movement particularly toxic for BIPOC.

— HCDE student

Black, Indigenous, and other frontline communities are disproportionately affected by climate issues. However, the mainstream climate movement often excludes or silences these voices.

After conducting our co-design sessions, it became clear that we did not draw a diverse sample from our recruiting methods. Our focus on decarbonization “solutions” and policy appealed to environmentalists of similar race and socioeconomic backgrounds and excluded the concerns of frontline communities.

Frontline communities tend to be concerned with the roots of climate issues, such as systemic racism, colonialism, and neoliberalism. These concerns are often dismissed or antagonized in the mainstream movement because they require critical reflection and are challenging to address.

We recognized that to be truly inclusive, we needed to explicitly center the concerns of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, people of color), frontline communities, and their allies. We branched off to explicitly create space exploring the systemic roots of climate issues.

Journey map to amplify voices

A “happy path” through a wicked problem.

Discursive design.

Analysis of a wicked problem.

Causal layered analysis (CLA).

The CLA vertical ontology describes how problems and their solution ideas can be articulated at four distinct levels.

Since the concerns of frontline communities often exist at the systemic level or beyond, we wanted to explore discursive design to unpack these deeply rooted issues.

“Part of the problem is different perceptions of the problem”

—SME participant

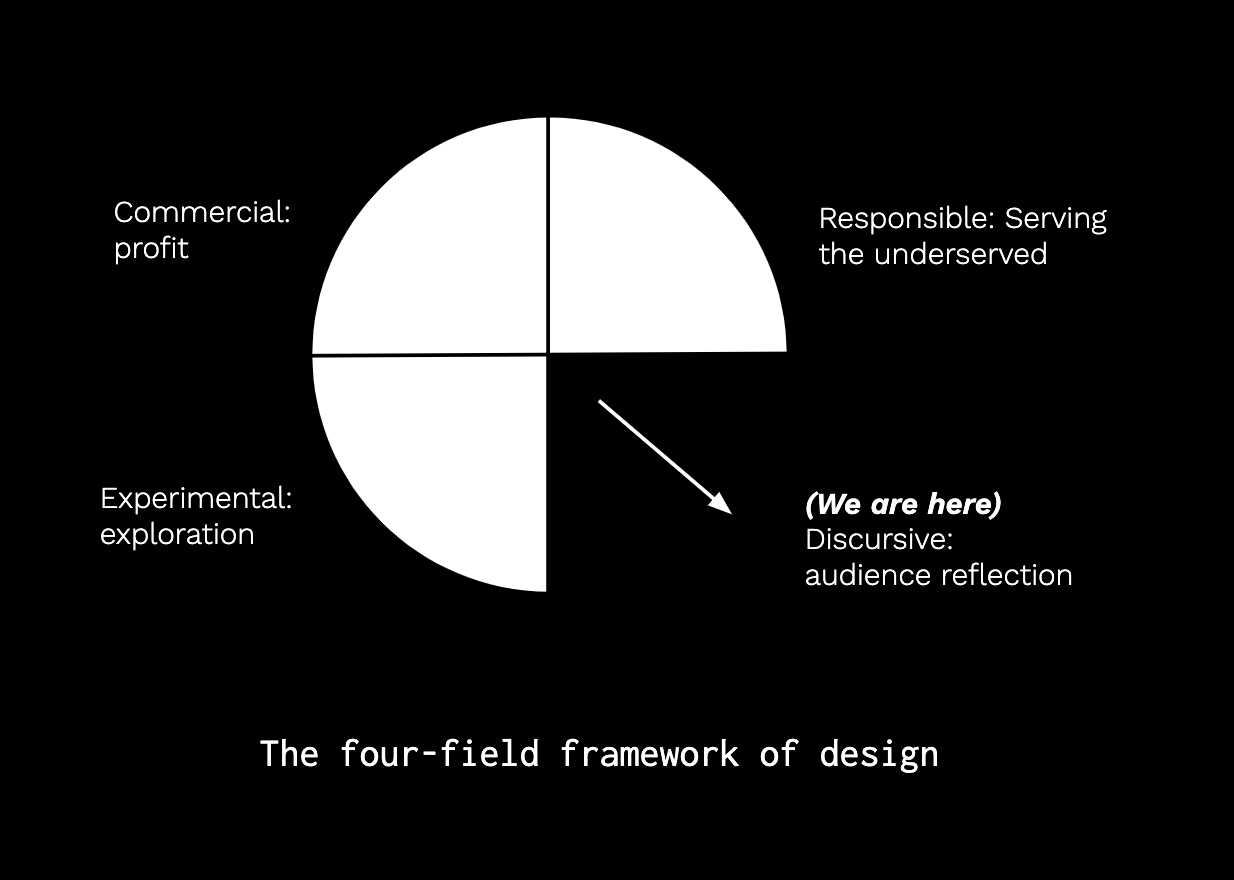

Discursive design and the four-field framework.

We turned to the field of discursive design to prompt reflection and assist in breaking down the problem.

The four-field framework of design developed by Tharp & Tharp, focuses on why things are designed rather than what or how. For the problem of climate change, discursive design seemed to be a natural fit.

As the authors discuss, discursive design can’t solve the unsolvable. But instead of avoiding or dealing with problems in a superficial way, it can prompt reflection which acknowledges and attempts to break down complexity with the hope of making progress towards a better state.

“Discursive design uses its tools to affect reflection, acknowledging and trying to unpack the complexity as a means of possibly progressing toward a preferred state or at least identifying attributes of what (wicked problem spaces) might look like or not look like.”

– B. Tharp & S. Tharp, 2019

Inspiration

Solarpunk.

Solarpunk is a speculative genre focused on positive futures of the post-climate crisis.

“When I scan solarpunk posts on Tumblr, I see constant defiance of the neoliberal attempts to stifle political imagination. More than just sketches and photos of vertical farms, I see solarpunk inspiring people to question the arrangements of modern life and, more importantly, propose alternatives”— Andrew Dana Hudson (2015)

Inspiration

Future visioning.

Our Symbiotic Life

and the SSPs.

Discursive project founded in the SSPs by Katja Budinger and Frank Heidmann.

The Shared Socioeconomic pathways (SSPs) were developed by a global modeling group, to look at 5 possible ways the world might evolve over the next century.

Instant Archetypes.

Future visioning new tarot card toolkit by Superflux.

Polak Game.

“Where do you stand” mapping by Stuart Candy and Peter Hayward and Superflux.

CMU metaphor cards.

Metaphor cards developed by the Imaginaries lab at Carnegie Mellon University

Workshop design.

Design concept.

Climate futures is a discursive, participatory design workshop intended to provide and accessible, creative and fun way of exploring different worldviews in the context of climate change.

Goals.

The goal of this workshop is to explore and practice expanding our worldviews in the context of climate. It should be fun, freethinking, and provide a bit of hope!

Who it is for.

To build broad coalitions within a diverse movement, we need to be open to conceptualizing a wide range of worldviews. This workshop is for people who see or want to see climate issues as systemic issues. This workshop might help community organizers who want to expand team members to alternate worldviews, or individuals who want a fun way to brainstorm with friends. Above all, this is for people who want to regain hope in the face of an insurmountable problem.

Logistics.

Over the course of 3 weeks we held 8 workshops and iterated incrementally to improve the flow and depth of our results.

1. Online tools

We used Miro and Zoom for whiteboarding collaboration and communication.

2. Small groups

For our studies, we found that 2-5 participants, including the facilitator was appropriate for achieving a high level of depth and tighter collaboration. We see potential for growth here.

3. Time

At least 90 minutes to run the workshop effectively.

4. Facilitator as active participant

Facilitators participating directly in the workshop performed the role as catalyst and sometimes holding the uncomfortability.

Warm up.

Three words.

Having participants note three words that describe their feelings about climate change is helpful contextually for the facilitators. Also part of our survey, these provide pertinent qualitative data.

Polak Game.

The purpose of this activity is to first acknowledge that we all experience the world differently, and that affects the way we view climate change. It’s important to be mindful of this as your participants start to brainstorm solutions in the next activity. Presumably we’d all like to move closer to the top-right quadrant, but our approach will be different depending on where we currently stand.

New pastiche scenarios.

Drawing from our inspiration to develop new socio-cultural contexts.

These are the three scenarios we developed for our workshop based loosely on three of the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs).

New metaphors & questions.

Providing scaffolding for creating new narratives.

1. Metaphor cards

We used a selection of the CMU collection, plus added 7 of our own that specifically referenced plants. During the sessions we suggested picking one card to build a narrative around, but people were open to take more.

2. Questions about your future life

We developed a series of questions to make the future life feel more tangible, but also to raise questions about the ethics and equity of the new worlds.

Creating new worlds.

Suppose it is 2040, and we live in a world in which we’ve “beat” climate change.

Try to envision what life might be like.

What is most important to you in this new life?

Workspace set up with an example of a filled out board.

Climate futures artifacts.

Workshop guide and anthology.

The research and design of the discursive branch resulted in two living artifacts.

1. An anthology that contains all the stories generated by our participants

2. A workshop guide for individuals and orgs with materials, method and sample script to conduct participatory climate futures workshops.

Results and future work.

Feedback from participants & mentors.

“It was so fun to explore those scenarios. We talked about them after for our whole walk!”

“I feel like a discussion of ethics was missing from each scenario we went through yesterday. Sure it was implied but not necessarily named, and I think it’s an important thing to highlight.”

“I noticed that a lot of the tech advancements we imagined in each scenario were similar, but the way we treat each other is totally different. It's also really refreshing to see a project that isn't directly about a privileged type of environmentalism.”

“I think your methods and outcomes were really important and your project was an innovative way to engage people in caring for our ecosystems.”

What’s next?

Add a more robust reflection piece.

Expand the workshop through longer, half or full day sessions, including more discussion of ethical concerns and/or more concrete climate actions.

Elevate the perspectives of frontline communities who are most affected by climate issues.

Increase the diversity of participants and facilitators and adjust it for:

Frontline communities

Community groups

Students

Small scale government teams